Narrative tells and summarizes while a scene puts the story of the page right on the stage, with concrete details, movements, and even dialogue.

narrative

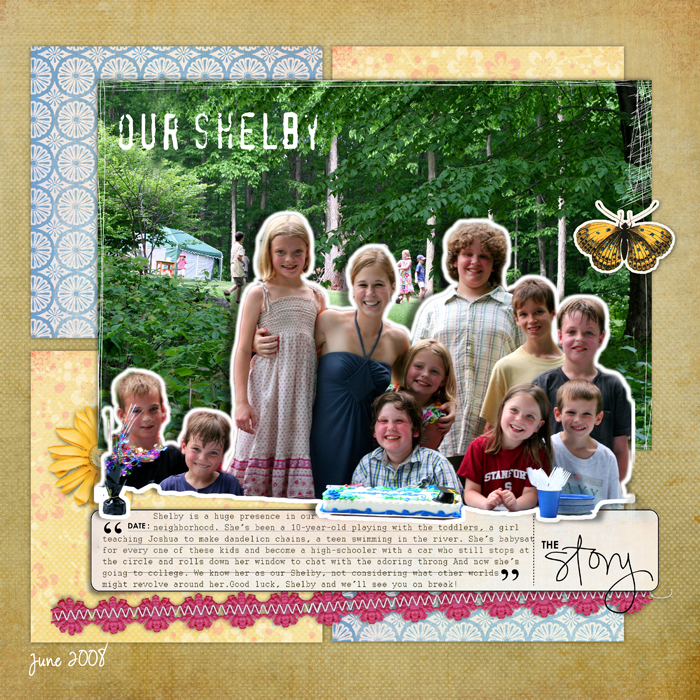

Take a look at the journaling in “Our Shelby.” It is written in narrative. Narrative is writing that tells and summarizes rather than putting subjects “on stage” speaking and/or interacting with one another.

Using narrative here works well because there wasn’t one incident I wanted to feature, but rather I wanted to convey how much all of us have taken Shelby into our hearts and lives the last eleven years. Note, though, that rather than relying on abstracts, I’ve used the lessons from Using Concrete Details in Your Scrapbook Journaling is Good. I’ve accumulated details to make my point.

JOURNALING: Shelby is a huge presence in our neighborhood. She’s been a 10-year-old playing with the toddlers, a girl teaching Joshua to make dandelion chains, a teen swimming in the river. She’s babysat for every one of these kids and become a high-schooler with a car who still stops at the circle and rolls down her window to chat with the adoring throng And now she’s going to college. We know her as our Shelby, not considering what other worlds might revolve around her. Good luck, Shelby and we’ll see you on break!

scene

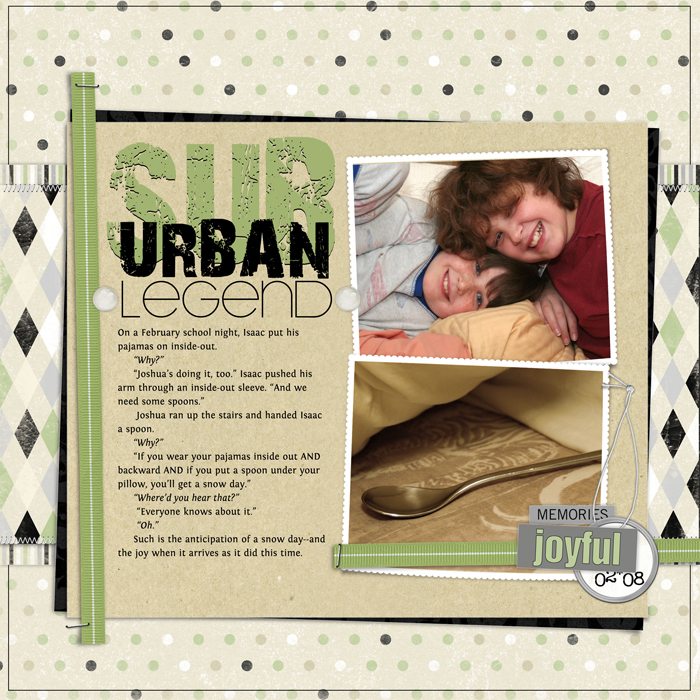

The journaling for “subUrban Legend” is written completely in scene. The photos set up the context of the scene and a combination of describing what the subjects are doing along with their dialogue conveys what’s going on. The result is a quick, fun page that captures a moment in our home. Pay attention to a couple of things in this journaling:

On a February school night, Isaac put his pajamas on inside-out. / “Why?” / “Joshua’s doing it, too.” Isaac pushed his arm through an inside-out sleeve. “And we need some spoons.”/ Joshua ran up the stairs and handed Isaac a spoon. / “Why?” / “If you wear your pajamas inside out AND backward AND if you put a spoon under your pillow, you’ll get a snow day.” / “Where’d you hear that?” / “Everyone knows about it.” / “Oh.” / Such is the anticipation of a snow day–and the joy when it arrives as it did this time.

- I used italics and then regular type to indicate a change of speaker. I did not include any “he saids” or “she saids” because the reader can figure out who is speaking from the context of the photos and the actual dialogue.

- Within this scene is something called a “beat.” A beat breaks up the dialogue and lets your reader visualize the subject in action. The beat here is: Isaac pushed his arm through an inside-out sleeve.

- This is the essence of what went on and was said, but it’s not perfectly accurate. The dialogue in fiction and even in creative non-fiction is not written the way people really speak. It is condensed and edited for flow and clarity — and for moving along without unnecessary details.

narrative and scene together

Much successful writing uses a combination of narrative and scene. A concise and relevant scene is a great way to break up narrative and keep it from getting dull.

“@ A Boy Who Loves Costumes” begins with quick scene setting and moves into dialogue that shows what was going on in these photos. While the entire story could have been told with narrative, including dialogue reveals other aspects of the people in your journaling and gives the writing more energy. A note, though: writing this kind of scene really requires making notes or scrapping the page very soon after the event if you’re going to stay true to what happened. (Again, you don’t need to record everything that was said — you can leave out the “ummms” or the phone call interruption.

Here, I begin with narrative to summarize information that would be tedious and impossible to provide in dialogue. Dialogue is used to both emphasize what’s important to my son and reveal more about his personality. The journaling ends with a transition back to narrative that summarizes the result of the conversation.

JOURNALING: You haven’t been crazy about the Middle School Socials, saying they’re hot and everyone just walks back and forth from the cafeteria to the gym to the bathroom. Boring and hot. And I haven’t pushed you to go–liking that you don’t feel a need to go just because many others are, liking that you enjoy just being at home on Friday night. When the announcement for the 6th grade social came home, though, I asked if you were going.

“I don’t know. They’re kind of boring.”

“It might be different with just your grade. And they’ve got a Luau theme.”

“How am I supposed to dress for that?”

“Wear a Hawaiian shirt.”

“Wait!” You perked up . . . “Could I get a TIKI mask?”

“Sure.”

“Great! I’ll go.”

And you did go. You and Sean got these tiki-face decorations from iParty and cut out the eyes and put on head straps. You and I even sewed a quick grass skirt out of card stock. The two of you called me about 20 minutes before the end of the party to say you’d had a great time and were now ready to play some video games. Apparently you both had a good time — did a little dancing, a little eating, a little talking before coming home for a fine sleep over. March 2008.

[lovejournaling]